See Something Say Something: Mandatory Reporting!

What is mandatory reporting?

Hospice clinicians advocate for their patients and their patients’ families. As a clinician, one of the most important ways that you can advocate for their patient is by engaging in mandatory reporting when you observe or suspect that your patient is being neglected or abused.

What is a mandatory reporter?

A mandatory reporter has an individual duty to report known or suspected abuse or neglect relating to children, dependent adults, or elders. These include:

- A child is anyone who is under 18 years old

- A dependent adult is anyone between 18 and 64 years of age who has physical or mental limitations that restrict their abilities to carry out normal activities or protection of their rights

- An elder is anyone 65 years of age or older

A reporter should report good faith beliefs or reasonable suspicions of abuse or neglect. The report will be confidential, and the identity of the reporter will be hidden from the public.

Who are mandated reporters?

State-specific laws specify several professions of mandatory reporters. These include professions such as:

- Social workers

- Teachers

- Healthcare workers

- Law enforcement

- Childcare providers

- Medical professionals

- Clergy

- Mental health professionals

The list of professions of mandatory reporters varies by state.

What is abuse?

Although we often think of abuse as physical abuse, remember that abuse can come in all different forms. For example, forms of abuse include:

- Physical abuse

- Mental anguish

- Financial abuse

- Sexual abuse

- Emotional abuse

Protect your patients by looking out for all of these different forms of abuse. No one deserves to be subject to any form of abuse.

How can you best protect your patient?

To best protect your patients, constantly be aware and on the lookout for any types of abuse or neglect. Hospice patients are vulnerable since they are often physically frail, dependent on others around them for support and care, and unable to advocate for themselves. As a healthcare worker, you need to advocate for your patient in the case of suspected neglect or abuse.

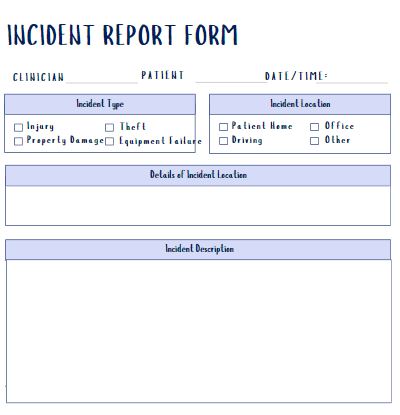

Continually assess the patient for any signs of abuse or neglect. Look out for any unusual behaviors. Follow any of your agency’s protocols in documenting any observations and conversations. If you identify concerns, share these concerns with the appropriate individual in your agency.

How do you report?

If your agency cannot provide you with clear guidance about how to report the suspected abuse or negligence, each state has websites that can provide you with that guidance. Each state has specific requirements on what you must report, required timing of reporting, and the like.

In addition, most states have reporting hotlines. Remember to be detailed and accurate when you file the report and to provide all the required information.

Why is it important for you to report?

Sometimes, you “may not want to bother” to report suspected abuse or you may feel “it is not your business to get involved”. However, here are two key considerations:

- As a healthcare worker and medical professional, you are a mandated reporter and as such, by law, you have a duty to report known or suspected abuse or neglect

- As a patient advocate and healthcare professional, you have an ethical duty to report instances of known or suspected abuse or neglect

Identifying abuse or neglect as early as possible is critical for the physical and mental health of the abused or neglected individual. Your actions can have profound positive consequences on your patient’s life. Remember: if you see something say something!

Where can you find out more?

- Mandatory reporting requirements

- Mandatory reporting overview – YouTube